ICON : ITW HUGH HOLLAND

Why is it always the same? Why is it that every time someone irresistibly draws me in, they live outside the system? The answer is perhaps simple and always the same: these people approach things differently. They are not victims of a stereotyped education and are willing to overturn the table if the rules don’t suit them, to create a world in which they would want to exist.

I say this, but I feel like I’m speaking about myself. Yet here, I’m talking about Hugh Holland. A master who recently left us, and whose last words I had the privilege of capturing. He was there before everyone else, doing what everyone today merely repeats—or rather, copies and pastes onto their mood boards.

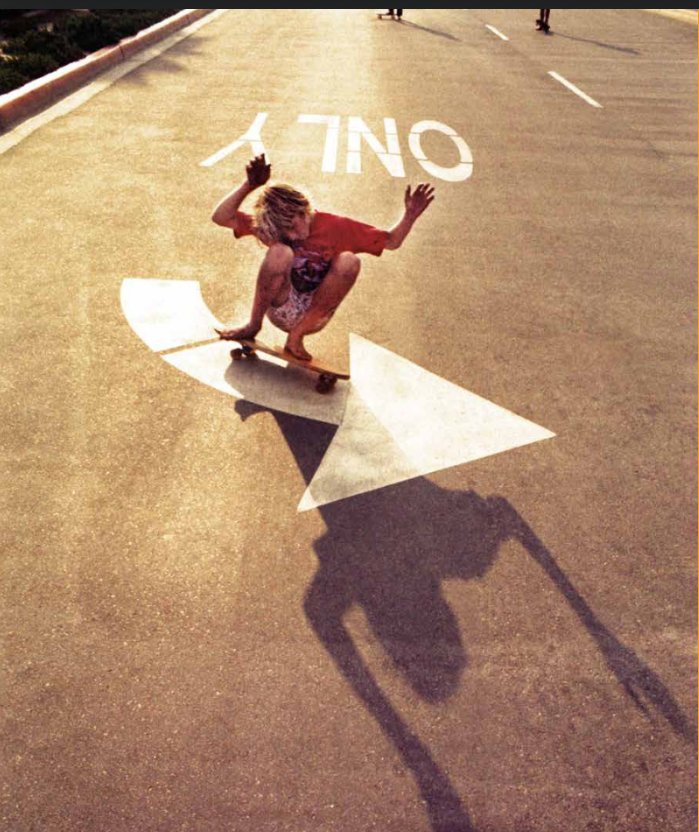

Now imagine a world before the inspiration supermarkets that are Pinterest and the like. A world where, to create, you had to face the unknown. In the early 70s, a young man named Hugh saw these skateboarders on his way to work. He had some knowledge of photography, and in just three years, what he was about to do would revolutionize the course of photography history—or at least, revolutionize my world.

Without him, I wouldn’t be here. Without him, we wouldn’t have proof that another world was possible. Until society came along and ruined everything. But that, you already know.

Sebastien Zanella: Before photographing skateboarders, who influenced you? Who were your inspirations?

Hugh Holland: A French street photographer from the 1930s... What was his name again? Oh yes, André Breton.

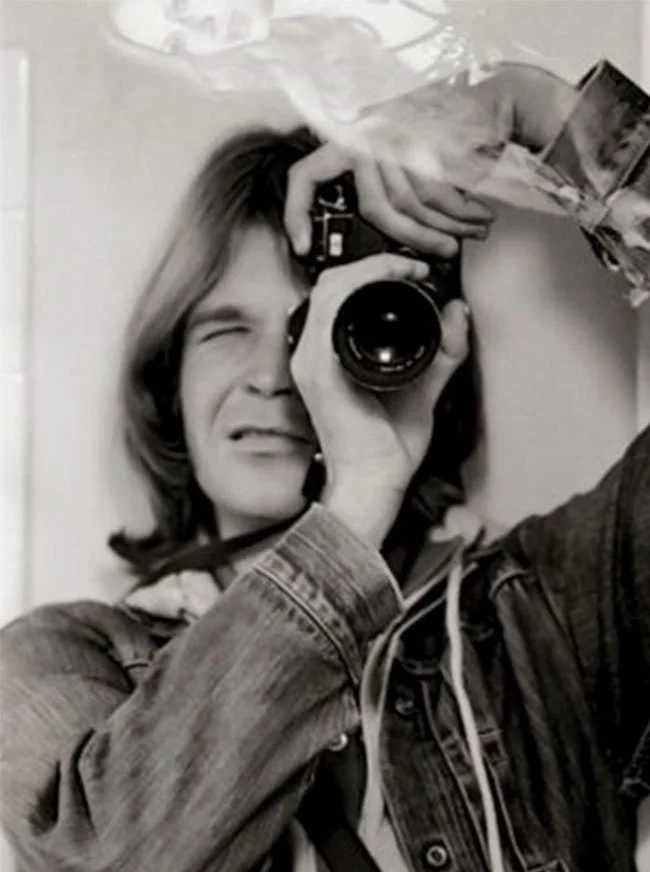

Sebastien Zanella: What’s interesting is that photographers at the time generally used 35mm cameras with wide-angle lenses. But you were already working in a very close-up approach. Few people did that back then.

Hugh Holland: Yes and no. I also mainly used wide-angle lenses. My primary lens was a 28mm mounted on a 35mm body. Later, I used an 18mm, even wider. But I also experimented with different focal lengths: a 45mm and even a telephoto for portraits.

Sebastien Zanella: You were using a Pentax, right?

Hugh Holland: Yes, I started with a Pentax because that was the camera I had. I only photographed skateboarding for three years: 1976, 1977, and 1978.

Sebastien Zanella: And then you stopped?

Yes, I’m not sure exactly why. I felt like skateboarding was changing completely. When I was photographing, skaters were everywhere, barefoot, shirtless. It was a raw, spontaneous scene. But after three years, everything changed. Logos started appearing, skaters began wearing branded T-shirts. Everything became more structured, more commercial. It wasn’t the same anymore for me, and I lost interest.

Sebastien Zanella: What’s fascinating is that your approach was very instinctive. Even today, few photographers dare to capture skateboarding in such a way. Many remain timid or hesitate to get as close to their subjects.

Hugh Holland: At the time, it was new for them too. They were happy to be photographed. They would perform tricks for me, pose naturally—there was a real connection.

Sebastien Zanella: After you stopped photographing skateboarding, what did you do?

Hugh Holland: I just went back to street photography, capturing a bit of everything, without a specific subject. In recent years, I’ve been shooting much less. It’s been a long time now… But I still have my camera, though today, I mostly use my phone.

Sebastien Zanella: What’s unique about your work is that you never shifted toward a journalistic approach to skateboarding. You always put aesthetics first. Few photographers of that era made that choice.

Hugh Holland: Yes…

Sebastien Zanella: You were older than them when you photographed them, right?

Hugh Holland: Yes, I was 30 at the time. And they were between 15 and 18.

Sebastien Zanella: Did you spend a lot of time with them?

I had a full-time job. I worked in a custom furniture finishing workshop in West Hollywood. So I could only shoot after work. That’s why many of my photos are taken at dusk. I loved how the air, the colors, everything changed at that time.

Sebastien Zanella: Which gives them a unique and beautiful light. At that moment, did you have a deep photographic culture, or was it purely instinctive?

Hugh Holland: I was doing action photography in general, not just skateboarding. I photographed people walking, running… I experimented. The right composition suddenly appears. You have to be ready to capture it instantly. I always say I don’t take pictures, I make them. The images are given to me. My job is to make something out of them.

Sebastien Zanella: A kind of intuition, anticipation?

Hugh Holland: Yes, especially with skateboarders. In a pool, they would repeat the same movements over and over. That allowed me to identify the key moment and capture it at just the right time—when they reached the peak, when they took flight.

Sebastien Zanella: When you did a sunset session with skaters, how many rolls of film would you use?

Hugh Holland: Usually five or six rolls per session.

Sebastien Zanella: So about 500 photos?

Hugh Holland: Yes, something like that. Back then, a roll contained 36 images.

Sebastien Zanella: When was your work rediscovered? You left skateboarding in the late ‘70s, but when did your work come back into the spotlight?

Hugh Holland: That happened much later. For a long time, no one was interested. But about 15 or 20 years ago, in the 2000s, people started rediscovering my photos.

Sebastien Zanella: How did that happen? Did someone approach you asking to see your images?

Hugh Holland: Yes, a friend of mine, George Mitchell. He came back to me, and I started showing him my prints, my books… He played a role in that rediscovery.

Sebastien Zanella: What’s fascinating is that every time you see one of your photos, you remember taking it. You still feel the wind, the light, the exact moment.

Hugh Holland: Yes, I remember every instant.

Sebastien Zanella: You’re working on a new book, which means you still have a lot of unpublished images?

Hugh Holland: He has tons of boxes full of slides. Thousands of images that have never been published.

ITW -The life of Chris Miyashiro

On the shores of O‘ahu, Chris Miyashiro does not surf against the elements , he enters into dialogue with them.

Since his earliest days, the ocean has been his home. He learned to listen to the wind, to read the curve of a wave like one reads the lines on the face of the world ; so that, like in life and surfing alike, he might find his balance.

In Hawai‘i, the native people have a word for this: Pono.

A philosophy in itself, embraced by the islands for centuries. The pursuit of harmony , in life and with all that surrounds it , is one of the foundations of Hawaiian culture. It is the culture that shaped Chris Myashiro into the man he is today.

Chris is a painter, navigator, shaper, filmmaker, surfer.

He moves between the lines of preconceived ideas, leaning on ancestral knowledge to approach the unknown and reshape its contours.

Through his Alaia boards, hand-carved from invasive trees, he transforms what destroys into what connects. It’s not just about riding , it’s about riding with intention. Each board is an offering. Each session, a silent prayer.

Ho‘oponopono, the elders say , a phrase that can be translated as “to correct what is out of balance.” A virtuous circle, not unlike the tumultuous movement of life and waves.

Chris knows it well: every time he’s set out to sea, it was so he could return to land with greater understanding.

And so, between action and surrender, Chris finds himself at home.

Balanced between two worlds.

Pono — because that is the word.

Can you introduce yourself and share what the ocean means to you?

Aloha, my name is Chris. I grew up on the beautiful island of Oahu, Hawai'i. Since before I can remember, the ocean has always felt like home. Surfing was naturally woven into every part of my life — it taught me to appreciate change, to slow down when life moves too fast, and to really listen.

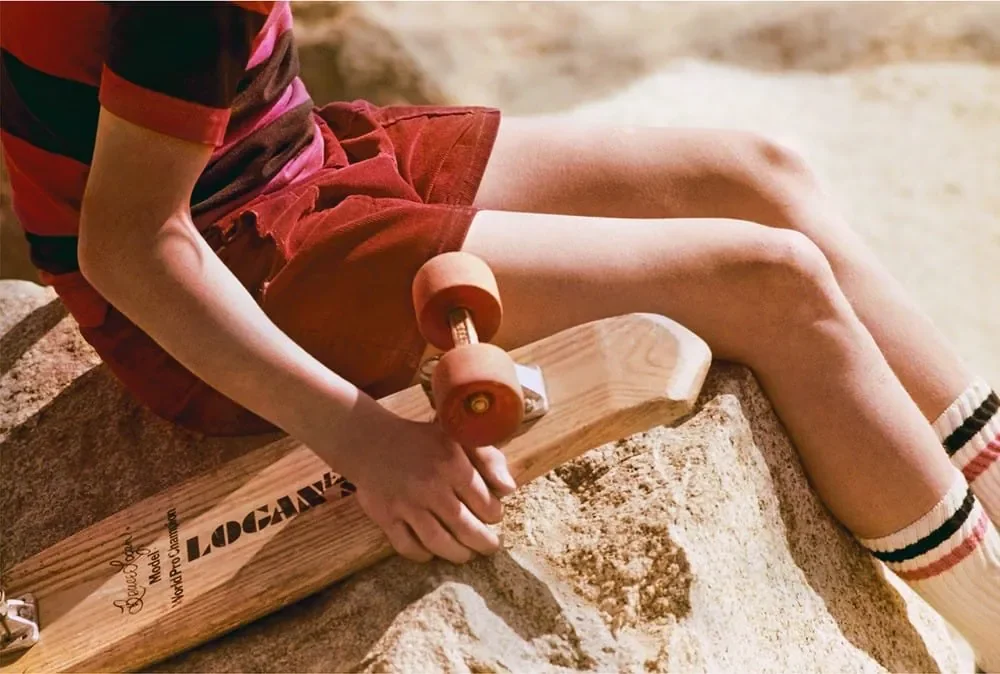

Tell us about the Alaia and its role in your life.

The Alaia has been pivotal in my surfing journey. Since I was young, it taught me how to read the ocean

not just to ride the wave, but to become one with it -

. It’s incredible to think it was once a living tree, and that its energy is now carried into the ocean. Riding an Alaia feels like dancing between the uplands and the sea — between two worlds.

You craft your own boards — what kind of wood do you use?

I make my Alaias from an invasive tree we call albizia. It grows fast, absorbs too much moisture from the soil, gets huge, falls down, and destroys everything around it. Thankfully, I have people in my life involved in reforestation who help remove these invasive trees and replace them with native ones. Turning albizia into surfboards feels like an act of circular design — giving life to what once took it away.

What other nature-based practices are part of your life?

Lately, voyaging has entered my world. It changed the way I see the ocean. Now the wind speaks to me — it teaches me how far I can go, how rare it is that we came to inhabit these islands, and how important it is to know our place. We are visitors here.

How do people usually react when they see you riding an Alaia you’ve built yourself?

Most people say, “You can actually surf that?” It takes patience and understanding. But once you ride something handmade and fully compostable, you start to see the world differently — as a connected, living being.

What’s your greatest memory so far?

The first time I went down the face of a wave on an Alaia — I realized space has rhythm, stillness holds energy, and water has no boundaries. The Alaia changed my perspective completely. You’re not just riding a wave, you’re dancing with its last breath. When the wave ends and you’re full of joy, you suddenly realize your breath matters. Everything you do has meaning. And kindness — always kindness — moves us forward. That’s what the Alaia teaches me: grace is everything.

What have been your biggest challenges, and what advice would you give to others?

The biggest challenge is sourcing wood responsibly. But my advice? Just start. Circularity isn’t about a specific culture — it’s about using what’s available and honoring it. Stop worrying about who might judge you. Everything you do matters. When you start, you learn what you really need — and what you don’t.

What message would you like to share with the people reading or watching this?

Love every little detail. Everything has a purpose — even imbalance. See what is good. Find what is beautiful. Let that guide your creativity. And love people.

Always, love people.

Ethan Lau, Listen to the Trees

In Honolulu, Ethan Lau moves barefoot between concrete and canopy, skating not to perform but to connect. Once a professional skater, he left trophies and shoes behind to follow a simpler path — one guided by trees, fruit, and presence. In this conversation, he shares what nature means to him, and how it continues to shape the way he lives.

What does nature mean to you?

Nature is a book whose pages stretch into infinity. But if you’re paying attention , you can read it. It begins just outside your door: noticing the wind, identifying a few plants or insects, and tuning into the subtleties. That’s nature. It’s not something far away ; it’s right here, whispering.

How does nature shape your lifestyle?

For me, it starts with what I eat. I want the best, most real food ; always. Nature gives it to us in rhythm. Mangoes come right when they’re meant to. Citrus arrives in perfect time. When you live with the trees, you begin to follow the seasons not on a calendar, but through your body.

What about nature in the city?

It’s funny ; we plant nature in the city to make ourselves more comfortable. But real nature ; it’s wilder than that. Like fruit hunting: sometimes I walk miles just to find a mango tree. You end up meeting people, asking questions, discovering places you didn’t expect. It’s not just about the fruit. It’s about the connection.

What role does movement play in your relationship with nature?

I used to skateboard every day. That was my introduction to flow ; finding lines through the city, navigating space with intuition. Surfing came later. It was like the ocean told me: “Slow down. Breathe. You’re part of this now.” When you’re on a wave, you’re just a punctuation mark in the ocean’s sentence.

Do you craft or grow anything yourself?

I’ve been learning to grow food and carve wood. One of the most beautiful things is making something from nothing ; something useful, with your hands. I believe every act of making is a way to root yourself deeper into the land.

Any advice for someone trying to reconnect with nature?

Start small. Go outside and be quiet. Ask yourself what’s growing near you. What birds do you hear? What phase is the moon in? It doesn’t have to be radical. Just present. Start noticing, and nature will notice you back.

And what has this path taught you?

That you don’t need much. That beauty isn’t in what you have : it’s in how you see. Nature teaches you how to let go, how to be humble, how to stay curious. And when you feel lost, it reminds you: you were never separate.

Icon ITW: TONY ALVA

In the 1970s, a legendary crew from Santa Monica, California, would forever change the simple act of riding a skateboard ; and in the process, the culture of surfing itself. The Zephyr Boys, later immortalized in the film Dogtown and Z-Boys. Without them, I probably wouldn’t be here writing these lines. Most likely, I’d be scrubbing boat hulls in the south of France, continuing the work of my ancestors.

Tony Alva, a prominent member and the charismatic leader of the crew, stood out as the most rebellious, the most anti-system. At just 19, in 1977, he became world champion of skateboarding. That title launched his life into a whirlwind of glory, travel, drugs, and chaos. Yet years later, that very chaos would lead him to develop a deep spirituality that still guides him today.

Now 68, he continues to ride the empty pools of Los Angeles with the same intensity. His style, forever infused with his obsession for surfing, carries a unique flow. This is what we talk about here ; but above all, how his rock’n’roll lifestyle gave way to the wisdom of a man who has stopped fighting in order to fully live in the moment.

Tony, can you start by introducing yourself?

I’m Tony Alva. We’re in Los Angeles, California. my daughter’s birthday was just a few days ago, she turned 35. She still looks like she’s in her twenties. She’ll always be my baby.

When you first started skating, did you already feel a spiritual connection, or did that come later?

My spirituality is tied to my sobriety and to being a surfer. When I was younger, I thought smoking weed, taking mushrooms, and listening to psychedelic music was spiritual. Music still is, but real spirituality for me comes from clarity, not from substances. I’ve been clean and sober for 18 years now. Staying on that path keeps me connected to God’s will for me ;that’s my spirituality.

So at first, drugs gave you an illusion of spirituality?

Exactly. Growing up in the ’60s and ’70s, people thought mixing sex, drugs, alcohol, and music was some kind of spiritual experience. But for me, it created fog. It blocked me. True spirituality is conscious contact with a higher power.

When I take photos, I try not to overthink but to accept the unknown. Do you see it the same way?

Yes. You have to surrender but not in weakness. Be actively calm and calmly active. In nature, panic will destroy you. If you stay calm, you make it through. Man’s ego is weak against nature; nature is overwhelming. I learned this through mistakes. Even after 50 years of professional skating, I’m still learning every session.

What is your faith based on?

That God constantly does for me what I could never do for myself. It’s not “my will be done,” but “Thy will be done.” My wisdom comes from letting God into my heart and soul. I don’t need to overthink : I keep it simple. Religion and spirituality are different. Religion is about rules; spirituality is direct connection.

You travel a lot. Do you study other religions?

Yes, everywhere I go I study local beliefs. Islam in Morocco, Buddhism in Asia, Hinduism in India, Christianity, Judaism, Hare Krishna… I don’t look for differences, I look for similarities. They’re all trying to reach God. Personally, I’m most connected to a mix of Christianity and Hinduism.

You often talk about ego.

The ego is the lie we tell ourselves about who we think we are. I can be arrogant, competitive, selfish. But today, prayer and meditation have replaced drugs and alcohol. I try to be honest with myself, recognize my flaws, and hand them to God. That makes me more empathetic with others.

You say you have an obsession with surfing.

Definitely. Skating is just cross-training for surfing. Nothing compares to the ocean. Surfing is like walking on water. It’s powerful, humbling, dangerous. You’re in the food chain ; a shark could appear at any time. That’s why it’s spiritual: you’re facing the immensity and you must be humble.

That connects you to the present moment?

Yes. Jerry Lopez, “Mr. Pipeline,” said the most important thing surfing taught him was to stay present. You can’t be in yesterday or tomorrow, you have to be in the wave right now. And grace ; that comes from God. But you only receive it if you’re calm enough.

You also knew ambition and competition.

At 19, I won the biggest skate contest in the world, broadcast on TV. I was world champion. That’s when I launched my brand and career. After that, I lived like a rock star ; sex, drugs, rock’n’roll. I had to prove I was number one. That was the gang mentality of Dogtown: show no one’s better than us.

What made you change?

Repetition. Making the same mistakes over and over ; that’s insanity. I realized it was destroying me. I quit everything: drugs, alcohol. That’s when I had a spiritual awakening. Within a year, I was a different person.

And now, how do you live?

I don’t compare my spirituality to others. I share what worked for me, but people have to do the work themselves. Smash the ego. Give up the vices. I live simply now ; I’ve been with the same woman for twenty years, in peace. Every morning I pray on my knees, meditate, do yoga. I take life one day at a time.